On Protest and Mourning

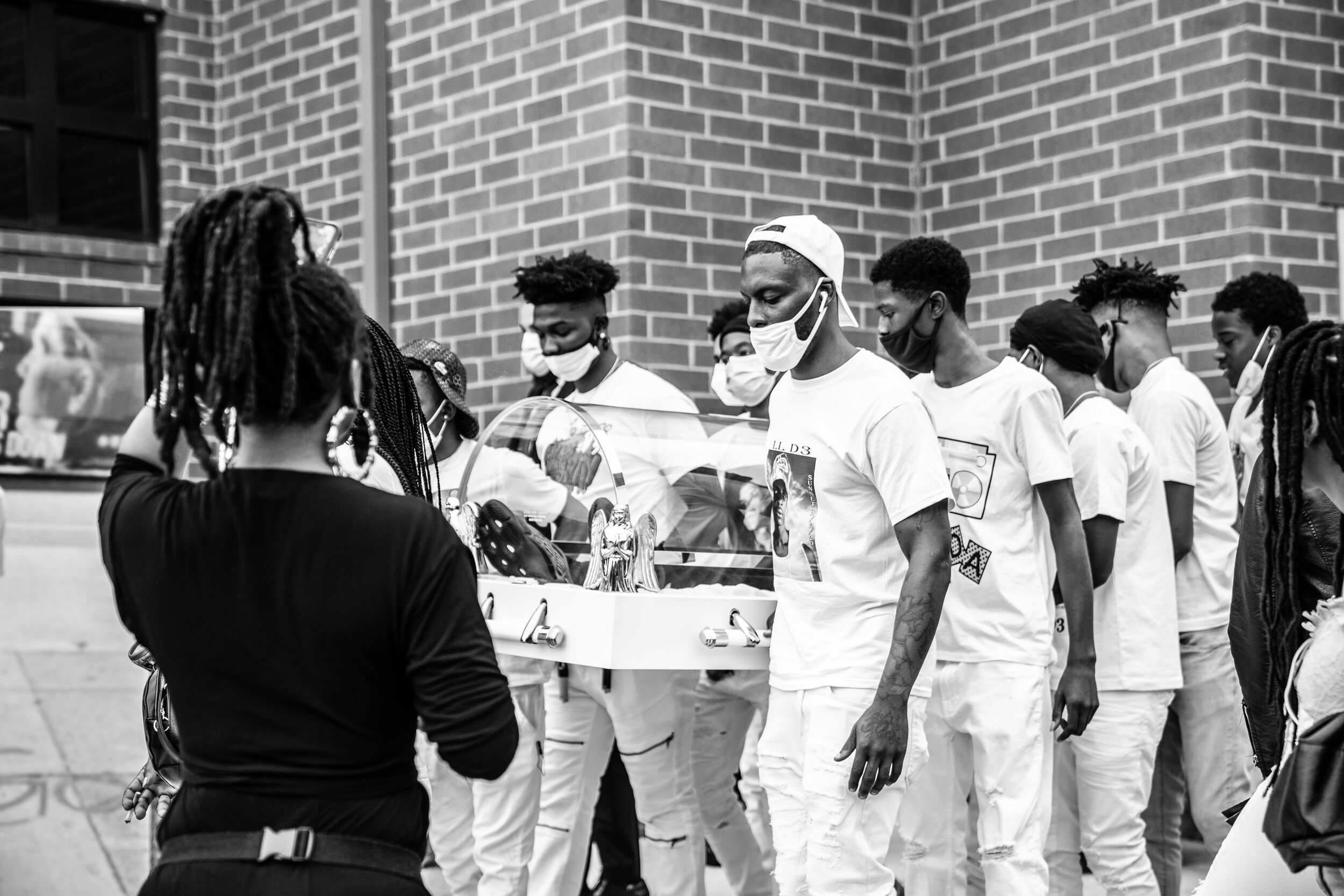

Photo by Vanessa Charlot

Turn It Up

On Protest and Mourning Prelude (OP&M Prelude) by Kareem Johnson is an original composition created in response and in tribute to the Black lives featured in this exhibition. Live protest footage and found sounds from the Black Lives Matter protests of Summer 2020 shape the ambiance, rhythmic, and melodic texture of this work. OP&M Prelude seeks out the collective grief buried under rage while dreaming for a sense of home that no longer feels homely.

“Protest is a form of mourning; and mourning is a form of protest.”

Our fractured nation continues to wrestle with a long condition of injustice: the brutal state and police violence perpetrated against Black lives. The last year, in particular, gathered and united us in unnecessary sorrow but necessary tumult—as a community, a country, and as global citizens, we mobilized an unprecedented response against systemic racism and violence.

CCCADI’s digital exhibition, On Protest and Mourning, brings together photographers and filmmakers who have recorded and borne witness to our uprisings and to our simultaneous insistence that the lives taken prematurely are mourned in public space. Gutted that we had to proclaim we matter, that we even have to say the words, we nevertheless see in their work our resolve to declare loudly anywhere and everywhere: Black Lives Matter. Too many times, when deep in the throes of rage and grief, those were all the words we could utter. In turn, these image makers, with roots throughout the Caribbean and African Diaspora, offered a visual language to articulate how we grappled with our anger and agony, hand in hand. Many of the moments they capture show the precarious—how we participated in protest and mourning throughout our neighborhoods and cities all the while knowing the possibilities of more terror, more violence, more death loomed all around.

Jon Henry presents poignant portraits of Black mothers across the US in intimate poses cradling, holding, embracing, and protecting their Black sons. They lay bare the visceral state of fear underscoring a vulnerable emotional landscape of motherhood: what it means to mother, to labor, to keep safe, only to lose a son in this America.

Vanessa Charlot portrays individual Black men—elders, young adults, teens, and boys alike—who took to the streets of St. Louis, Missouri after George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota. Charlot shows us a generation of men long steeped in the soundtrack of protest and the poetics of mourning, caught in an arduous, unending procession of grief.

Through his lens on the scourge of violence in Chicago, Carlos Javier Ortiz films a city simultaneously immersed in its inconsolable loss as well as its desire to rebuild. Heard in the chants and laments of the documentary’s protagonists, is a city composing a collective elegy for the lives systematically silenced.

In Dee Dwyer’s images of Southeast, Washington, D.C, the community’s youth watch with equal parts rage and resolve as one of their own is laid to rest. In these witnessing children we are reminded of what Audre Lorde told us, “If they cannot love and resist at the same time, they will probably not survive. And in order to survive they must let go.”*

Mired in the onslaught of indignity and devaluation of Black lives, Terrence Jennings searches for honor and dignity in the sea of faces, the masses that marched in solidarity throughout New York City’s streets.

Through a dual presence and absence of the self in landscape photographs set in the American South, Nadia Alexis considers the Black women we have lost to “state and interpersonal erasure,” whose names we are yet to know, whose spaces for mourning were stolen.

Collectively, these visual narratives help us to navigate questions such as: How do we record our outrage against Black death as well as affirm Black life? While we engage in protest and uprising, how can we also mark the lives that have been irreparably damaged or lost? How do we create rituals and make spaces for mourning? How do we honor our individual and collective grief, privately and publicly?

Protest is a form of mourning; and mourning is a form of protest. Throughout these images we see a consistent narrative, a shared language, a call to action: we must resist slipping into numbness, we must always cry out against a state’s militarized violence, against the emotional and mental brutalities it wields. And, as a matter of survival, we must always cry out for the Black lives loved and lost.

—Grace Aneiza Ali, Curator

*Audre Lorde, “Man Child” in Sister Outsider, 1984

Stranger Fruit

By Jon Henry

Who is next? Me? My brother? My friends? How do we protect these men?

This body of work, Stranger Fruit, is a response to the senseless murders of Black men across the nation by police violence. Even as citizens increasingly record and document these brutal acts with their smartphones and dash cams, more lives continue to get cut short due to unnecessary and excessive violence.

Lost in the furor of media coverage, lawsuits, and protests, is the plight of the Black mother. Who, regardless of the legal outcome, must carry on without her child.

I set out to photograph mothers with their sons in their environment, reenacting what it must feel like to endure this pain. The mothers in the photographs have not lost their sons, but understand a sobering reality: this could happen to their family. In some of the photographs in Stranger Fruit, the mother is portrayed in isolation, reflecting on absence. When the court trials are over, the protesters have gone home, and the news cameras are gone, it is the mother who is left. Left to mourn, to survive.

The title of the project is a reference to the song “Strange Fruit.” In its powerful verses, the protest song decries the lynching of Black Americans during the 20th century. Now, instead of Black bodies hanging from Poplar Trees, these fruits of our families, our communities, are being killed in the street.

All images courtesy of Jon Henry. © Jon Henry

Jon Henry is a visual artist working with photography and text. His work reflects on family, socio political issues, grief, trauma, and healing within the African-American community. Read more about the photographer here.

Montgomery, AL

North Miami, FL

Little Rock, AR

Groveland Park, IL

So, we may have gotten rid of the nooses,

but I still consider it lynching when they murder Black boys

and leave their bodies for four hours in the sun.

As a historical reminder

that there is something about being Black in America

that has made motherhood sound

like mourning.

— The Joys of Motherhood by Mwende Katwiwa

Am I Next?

By Vanessa Charlot

These photographs show the generational impact of racial injustice upon the Black male body in America. The purpose of my work is to humanize the Black experience. I seek to capture everyday life in Black communities, providing an intimate look into the stories of those who commonly don’t make it into America’s public discourse.

I have been documenting Black life and various facets of Black liberation for eight years. Photographing the Black Lives Matter movement in St. Louis, Missouri, a city that is full of racial and economic inequality and exists in the harrowing shadows of the Ferguson Uprising, forced me to face the weight of structural dehumanization in a visceral way. Through my photographs it became clear that Black America was facing two existential threats: police brutality and coronavirus. The stoicism of the men in the crowd, even through their melancholic rage, showed the pain that they often suffer in silence.

There was nothing new about the circumstances around the death of George Floyd. America has participated and been complicit in the lynching of Black bodies since its inception. This violence is an intrinsic American value. These images of Black boys and men across all ages speak to the long standing pervasive nature of the same racial injustice that birthed one of the largest civil rights movements of our times. Moreover, it addressed the inextricable thread between protests and mourning. That Black communities exist in a perpetual state of mourning and protests has been, and still is, one of the many physical manifestations of this expression.

All images courtesy of Vanessa Charlot.

© Vanessa Charlot

Vanessa Charlot is a documentary photographer living and working between St. Louis, Missouri and Miami, Florida. Read more about the photographer here.

Men like me and my brothers filmed what we

Planted for proof we existed before

— The Tradition by Jericho Brown

We All We Got

By Carlos Javier Ortiz

We All We Got captures the poetic language of the streets: police helicopters flying over the city, music popping out of cars, people talking trash on the street corners, ambulances on the run, and preachers hollering for the violence to stop after another young man is senselessly gunned down in the streets of Chicago.

I n this current moment of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the country’s renewed focus on racialized violence, police brutality, poverty and marginalized communities, We All We Got is an elegy of urban America. The film is an intimate portrait of people affected by violence: including community activists, kids, and cops. It navigates the tragedy and persistence of families impacted by violence, the perseverance of affected families, and the outpouring support of local leaders and residents who highlight these social issues in Chicago.

In my work to illuminate the effects of violence in neighborhoods often overlooked, I aim to highlight both beauty and imperfection, hope and resilience. I position my work within the fields of documentary filmmaking and sociology to address the contemporary manifestations of these long-term, evolving problems. To illuminate a place, like Chicago, I highlight the physical landscape and the built environment to give depth to the communities in which people come to live their lives. By immersing people in a space, I seek to create moments that engender empathy and address alterity. I’m trying to go beyond the headlines and show these are real people.

This documentary highlights the lives of my fellow brothers and sisters who are often rendered invisible and silenced, their stories reduced to stereotypes. We All We Got is a resistance to their invisibility.

We All We Got | 2014 | 8:58 | United States | English | B&W. Courtesy of Carlos Javier Ortiz.

Carlos Javier Ortiz is a director, cinematographer, and documentary photographer who focuses on urban life, gun violence, racism, poverty, and marginalized communities. Read more about his work here.

in these vibrating hours where the corners talk back

need I simply run my tongue along the granite sky and live

— In the Middle of the Burning by Canisa Lubrin

Justice for Deon Kay

By Dee Dwyer

In these images, a community is protesting and mourning the loss of yet another young Black life. Last September, Deon Kay, who had just turned 18 years old, was fatally shot by a police officer in a Southeast neighborhood in Washington, D.C. In these images—men, women, and young children who are hurting and enraged as they try to make sense of exceptional loss, who are in grief and watchful silence as Deon is laid to rest—I see the pain caused from several failed systems in America. I see the resilience from Black people who are fighting for peace and fair opportunities to live. I see and hear the screams for justice for Deon Kay.

Southeast is a beautiful place and full of strong D.C. Black culture. Yet, it needs more genuine documentation. It is a neighborhood that is underserved and often misrepresented in the media. As a photographer, I’m invested in photographing the “misunderstood.” I hope my work can clarify misconceptions of communities like these that are too often economically disadvantaged. In Southeast, there is a constant need for assistance coupled with a relentless fighting for the betterment of Black lives. While the injustices on Black bodies continue to happen and the people in Southeast have grown weary, they show a determination to fight to exterminate the ongoing wildfires burning through our community.

All images courtesy of Dee Dwyer. © Dee Dwyer

Dee Dwyer is a photographer from Southeast, Washington, D.C. She aims for her work to serve as a “visual voice for the people” with images that expose a subject’s truth and adversities and elevate a community’s beauty and culture. Read more about the photographer here.

But what causes it to rise. Hey, Black Child,

You are the fire at the end of your elders’

Weeping, fire against the blur of horse, hoof,

Stick, stone, several plagues including time.

— For Black Children at the End of the World—and the Beginning by Roger Reeves

I saw honor and dignity, too!

By Terrence Jennings

From the spring of 2020 through the summer/fall months of 2020, I documented New York—a city whose people have always been at the forefront of the calls for racial justice. The photographs range from East 86th Street, mere steps from the mayor’s residence Gracie Mansion, across the Brooklyn Bridge, and at the front of the Barclay Center. At each occasion, hundreds and at times thousands of New Yorkers gathered in solidarity—sometimes quietly in silent protest, sometimes in prayer—to disavow hatred, oppression, and violence.

As a news photographer and photojournalist, my natural inclination is to move toward narratives that need to be further explained through a visual perspective. Photographing the masses in protest and their unpredictable physical nature can be challenging. I am constantly questioning how to proceed using dual concepts of honor and dignity in documenting what is at play. In these protests throughout New York City last year, I saw a collective mission to reclaim a spirit of goodness. This is what I found to be important in the grand scheme of it all: the honor and dignity carried in the hearts and minds of the masses who sat in silence in front of the mayor’s home or who walked across the Brooklyn Bridge with their arms interlocked.

All images courtesy of Terrence Jennings. © Terrence Jennings

Terrence Jennings is a photographer living in Brooklyn, New York. His work focuses on documenting the African-American experience and issues of social justice. Jennings is a member of Kamoinge, the African-American photographers collective founded in 1963 and is the founding curator for the photography public program series, Visually Speaking. Read more about the photographer here.

Our labor has become more important than our silence.

— A Song for Many Movements by Audre Lorde

What Endures

By Nadia Alexis

In What Endures, I interrogate questions of survival and danger concerning the lives of Black women who experience disproportionately high rates of state and interpersonal erasure and violence in the U.S., Haiti, and throughout the African Diaspora. From survivors of domestic and sexual violence to those who are re-traumatized by the legal system and community members that fail to support them to those who’ve been targeted or murdered by law enforcement. I too am a descendant of women survivors grappling with personal traumas. While our experiences can be characterized by suffering, we also survive, transcend, and reimagine the self and what’s possible for our futures.

Using my body as the ‘Woman in White,’ I perform an effective relation of the Black female subject to the natural landscape, asserting it as a place of freedom and communion, as well as a place of haunting and alienation. My choice to make the photographs in Oxford, Mississippi is informed by the histories of plantation slavery and gendered violence against Black women’s bodies and spirits in Southern landscapes and others.

As I consider how our humanity is still being disregarded in pandemic times, I present these images as a form of homage to the departed and the living. They are also a form of embodied resistance to that which and those who have inflicted harm upon us. I seek to unearth questions and truths informed by subjective narratives, mythologies, and spirituality, examining how we hold on to memories and discover liberation through their release.

All images courtesy of Nadia Alexis. © Nadia Alexis

Nadia Alexis is a poet, photographer, educator, and organizer born in Harlem, New York City to Haitian immigrants and currently based in Oxford, Mississippi, where she is a creative writing PhD student at the University of Mississippi. Read more about the artist here.

It is our grief

heavy, relentless,

trudging

us, however resistant,

to the decaying and rotten

bottom of things:

our grief bringing

us home.

— Turning Madness into Flowers #1 by Alice Walker

Turn It Up

Photo by Dee Dwyer

The Lists

The following Reading, Viewing, Listening and Book Lists supplement the voices featured in On Protest and Mourning. They continue the conversation by offering a deeper dive into protest and mourning, the impact of racial violence on Black minds, bodies, and spirits, policing as an agent of white supremacy, the different faces of policing, as well as how to heal and protect one’s self and one’s community when mobilizing against injustice. These materials—from key pieces of journalism and scholarship to poetry anthologies to responses in dance to a resistance podcast—engage the many ways we can begin creating a world where systemic war on Black lives comes to an end.

The Reading List

Whose Grief? Our Grief by Saeed Jones

Black Lives Matter Poetry Anthology by Poets.org

Racism Is Terrible. Blackness Is Not. by Imani Perry

The Trayvon Generation by Elizabeth Alexander

The Unbearable Grief of Black Mothers by A. Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez

Law Enforcement Violence Against Women of Color & Trans People of Color: A Critical Intersection Of Gender Violence & State Violence by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence

Police Killings and Black Mental Health by Greg Johnson

This Is What You Get by Ashley Reese

US Protest Law Tracker by the International Center For Not-For-Profit Law

The Black Art of Escape by Casey Gerald

Dismantling Rage: On Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider by Mahogany L. Browne

The Viewing List

How Response to George Floyd’s Death Reflects ‘accumulated grievance’ of Black America with Eddie Glaude and Amna Nawaz

Invisible No More: Resisting Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color in Troubled Times hosted by the Barnard Center for Research on Women

Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at MoMA

Black Bodies Sonata by Kayla Farrish

Picturing Black Deaths: A conversation with Emily Bernard and Jelani Cobb

Giverny I (Négresse Impériale) by Ja'Tovia Gary [info]

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America at The New Museum

Alright music video directed by Colin Tilley for Kendrick Lamar

Moonlight (2016) film available on Netflix

Noname: Tiny Desk Concert featuring Noname

The Listening List

The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning by Claudia Rankine

Resistance Podcast: A 1, 2, 3 part series on a collective of racial justice activists.

Youth Leading Protests for Black Lives & Police Abolition with Jamila Washington, Jeremy Cajigas, and Tagan Engel

Ruth Wilson Gilmore Makes the Case for Abolition with Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Chenjerai Kumanyika

‘Notice the Rage; Notice the Silence’

with Resmaa Menakem

Ep040: #GoodAncestor Dr. Mariel Buquè on Breaking the Chains of Intergenerational Trauma with Layla Saad and Dr. Mariel Buquè

Sustaining Ourselves When Confronting Violence featuring Kandace Montgomery and Miski Noor

Tricia Hersey On Rest As Resistance with Tricia Hersey and Ayana Young

Photo by Terrence Jennings